Amid continued statewide housing shortfalls, some hope for renewed efforts

Lack of housing a major hurdle for workforce attraction

Before leaving office, former Gov. Doug Burgum proposed spending $96 million on a housing initiative for the current biennium.

Upon assuming the governor’s office earlier this year, Kelly Armstrong upped the ante, proposing $105 million toward similar housing initiatives.

In the end, the state legislature devoted $35 million total toward housing solutions during the last session, with $10 million going to address homelessness.

That left a bucket of $25 million for the state’s housing incentive fund, which creates a super-competitive situation for communities hoping to tap that funding.

Commerce Commissioner Chris Schilken, who served as commissioner for South Dakota’s Office of Economic Development before taking up his new position earlier this year, saw firsthand in Pierre how a strong commitment to overcoming housing roadblocks can make a difference.

South Dakota passed a $200 million housing initiative in early 2023 focused on incentivizing infrastructure upgrades that would spur more housing development.

Through this program, over 70 projects were launched across the state that led to the addition of 12,000 new housing units in just two years.

Schilken said the biggest challenges almost any state in the region faces are workforce, housing, and childcare.

“Housing really is a dominant factor in all of those,” Schilken said. “So, you need to probably start with the housing piece of that puzzle, because that's going to help with the workforce piece, and ultimately some of the childcare.”

A key component of Armstrong’s plans was a $50 million program to incentivize infrastructure improvements with grants to lower the cost of water, sewage, power, communications, and transportation needed to support new housing.

The plan had similarities to what was successfully rolled out in South Dakota.

Most of the funding targeted communities under 20,000. Matching funds from political subdivisions, local developers and other funding sources within local communities would have been required had the program gone through.

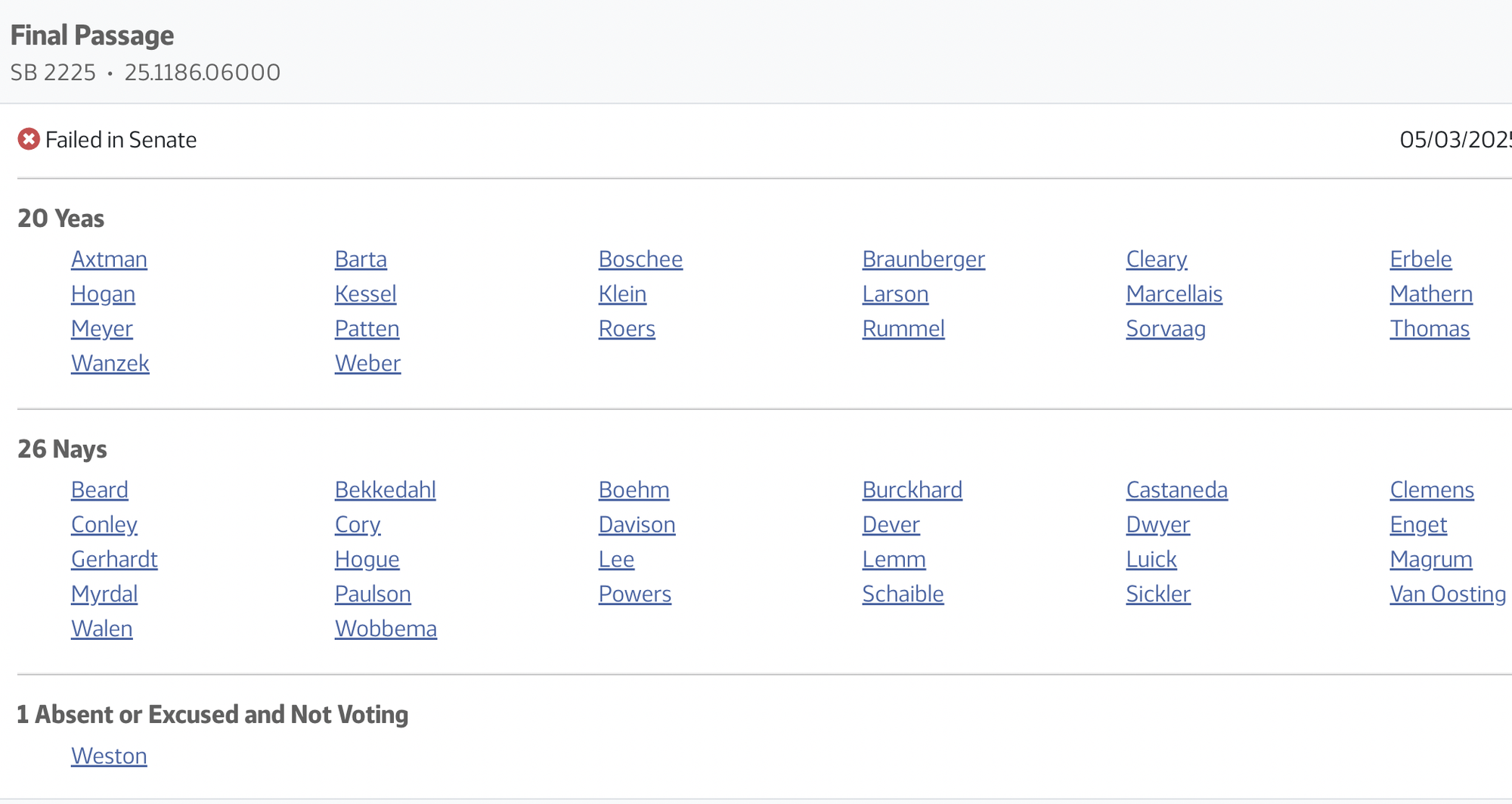

That bill, SB 2225, failed in committee in the wee hours of May 3 just before the conclusion of the legislative assembly.

For those closely following the housing shortage saga, failures of the legislature to back more robust action have postponed inevitable expenditures to the long-term and made it more difficult to attract workers in the short-term.

Constraints on growth

In the northeast part of the state, a recent survey of businesses and communities conducted by the nonprofit group Red River Community Housing Development Organization (CHDO), found rural areas in Grand Forks, Nelson, Pembina and Walsh counties need an extra 4,800 housing units by 2030 to fulfill workforce needs.

Of those, over 2,300 are in rural Grand Forks County alone. The study did not include the city of Grand Forks.

“It’s affecting the economy’s ability to grow,” Lisa Rotvold, RRCHDO executive director, said of the shortfall in new builds. “People don't realize all the businesses that are functioning out there and there's really great things happening out in some of our rural communities.”

Rotvold said the survey identified a lack of buildable lots as one of the major barriers for rural communities. Towns have already expanded to their limits, with constraints on growth due to the floodplain and high-value agricultural land.

“So that is a constraint that I think a lot of small towns are kind of battling right now, where they're at a point where they could grow, and they could see some good economic development or growth,” Rotvold said.

A Spark Building Initiative led by RRCHDO has helped add two homes in Larimore and another two in Lakota, with several more in the works in other towns in the region.

Amie Vasichek, city auditor in Lakota, said Spark has been great for the town, but that more is needed, which is why she testified in support of SB 2225 earlier in the year.

“We do have a need for more workforce here, but there’s no place for people to live either,” Vasichek said. “All of our apartments are filled. We have a need for multi-unit housing, but we need to find somebody to take that on because it’s a huge cost, and there’s not a lot of profit in there if at all for somebody to build something like that.”

That lack of housing impacts town businesses, particularly those with secure but not the highest paying jobs like local gas stations and other small businesses, she said.

“Housing is really tight, and in some of these smaller communities it’s to a point where it causes issues with trying to grow,” said David Klein, executive director of the Great Plains Housing Authority based out of Jamestown.

Klein said the great thing about the failed housing infrastructure plan was how it targeted smaller communities, where it is often difficult to develop housing because developers are focused on the major urban areas where a lot of infrastructure is already in place or easier to scale.

Higher material and labor costs mean it is more costly to build on or develop infrastructure for a single lot as opposed to developing the infrastructure for several lots at once, Klein said. More lots in one place could drive interest from developers.

“Not having that puts things back further,” he said of the failure of the legislation.

Corry Shevlin, executive director of the Jamestown/Stutsman County Development Corporation, said there’s a need for all levels of housing in his region.

Jamestown had been primed and ready to roll out projects if the legislation had passed.

“We had to reevaluate where and if our dollars would have the same impact,” Shevlin said. “We recognize that the problem’s not going to go away. We would have loved to see that program funded. It was a great proposal, and I’m hoping it does return in future legislation.”

Shevlin said the organization was ready to put forward $1 million for a community match if the bill had gone through. He’s hopeful of getting a couple projects through local initiatives moving by the end of this construction season, but the clock is ticking.

Schilken said he expects some form of Armstrong’s proposal to be resurrected in the next legislative session.

“Although we’re disappointed it didn’t pass, I think it started the conversation and really brought a lot of different people into that conversation,” Schliken said. “Those are good things to take from it and we can put together some legislation to bring back next session.”

Missing middle

Besides the smaller rural communities, other larger urban centers have difficulty attracting and retaining young and mid-level professionals because of housing imbalances.

Most of the housing available is either on the high or the very low end of the spectrum with what’s in the middle coming and going from the market in a flash.

Future housing proposals should also have a “move up strategy” so that those in entry-level housing can move up the ladder in five to 10 years, freeing up housing for those coming in, said Nick Hacker, CEO of the Title Team and a legislative committee president for the North Dakota Land Title Association.

“There's a pipeline here that's really important, and if any part of the pipeline is kind of broken, in the long term it will be a struggle,” Hacker said. “We have to pay attention to the missing middle.”

Daniel Stenberg, economic development director in McKenzie County, sees a similar situation in Watford City. Higher labor and construction costs often lead to the building of higher-end homes, missing out on the mid-range market. That impacts the ability to retain workers.

“We’ve got people that come in and they live in an apartment for a year or two, but they want to bring their family in and make themselves part of the community,” Stenberg said. “From a retention standpoint, you get people a lot more rooted if they have a house, they’ve built some equity, they’ve got kids in the school system.”

Stenberg said he hopes any future state-level solutions would recognize investments already made in shovel-ready lots in places like Watford City, with the potential to use that funding toward down-payment assistance.

“It moves the builders to build, and then the buyers to be able to qualify to purchase these houses,” Stenberg said.

The North Dakota News Cooperative is a nonprofit news organization providing reliable and independent reporting on issues and events that impact the lives of North Dakotans. The organization increases the public’s access to quality journalism and advances news literacy across the state. For more information about NDNC or to make a charitable contribution, please visit newscoopnd.org. Send comments, suggestions or tips to michael@newscoopnd.org. Follow us on Twitter: https://twitter.com/NDNewsCoop.